Born 1798 (99?)

Birthplace Massachusetts

Died 1873

Grave Site Mt. Hope Cemetery, Rochester, NY

Contribution Quaker anti-slavery activist and women’s rights advocate

Rhoda DeGarmo lived with her husband, Elias DeGarmo, in Gates, New York. They were neighbors of Daniel, Lucy, Mary and Susan B. Anthony.

DeGarmo was an early member of the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society (WNYASS). She joined in 1842, the year that the Society was established. In 1845, she was appointed chair of the Society’s counselors (a group which has been likened to an executive committee). As a woman member of WNYASS, DeGarmo was also involved in the organization of Anti-Slavery Fairs, usually held annually. The purpose of the fairs was to raise funds to support the anti-slavery cause and to raise awareness of the plight of slaves and the evil of slavery. The seventh annual fair, held in 1849, caused a controversy when WNYASS members invited “all classes and colours” to sit down “at one table” to share a great feast.

DeGarmo was also a part of the network of anti-slavery activists who made up the Underground Railroad. Her home often provided refuge for fugitive slaves on their way to Canada. She was a close friend and co-worker of the Anthonys in the anti-slavery movement, one of the group which met regularly on Sundays at the Anthony farm during the 1850s to discuss various reform issues.

As a member of the Society of Friends (Quakers), DeGarmo was active in the Farmington (New York) Quarterly Meeting. She was on a committee that first considered the “Junius” proposal in 1836. This proposal, which came from the Junius Monthly Meeting in Waterloo, New York, sought to make men’s and women’s meetings in the Society of Friends more equal. She was also among those Quakers who would, a decade later, take issue with the ministers and elders of the Genesee Yearly Meeting of Friends. While the ministers and elders of the Society of Friends considered slavery to be evil, they disapproved of many of the activities of anti-slavery advocates such as DeGarmo. In response, radical Quakers like DeGarmo claimed that ministers and elders should not have the right to limit “activities of conscience” of individual members. The controversy came to a head in the Genesee Yearly Meeting in June, 1848, when the radicals, including DeGarmo, walked out. She was “released” (no longer considered a member) from the Genesee Yearly meeting in 1849.

During the late 1840s and 1850s, DeGarmo was active in the Spiritualist and temperance movements. As a Spiritualist, she was an early supporter of the Fox Sisters. In the fall of 1848, Kate and Margaret Fox heard strange “rappings” in their home in Hydesville, New York. They declared that these “rappings” were messages from the dead, and that they themselves could act as mediums to interpret these messages. DeGarmo was one of a small group of followers that supported the sisters even before they achieved public acclaim.

DeGarmo’s belief in the temperance (abstinence from alcoholic liquors) cause led to active participation in that movement in the early 1850s. When Susan B. Anthony was prevented from speaking at a Sons of Temperance meeting in 1852, Anthony began to plan the establishment of a woman’s statewide temperance society. A call was put out and almost five hundred women came to a meeting to form the Woman’s State Temperance Society. At the meeting, held on April 20th and 21st, 1852, Elizabeth Cady Stanton gave several rousing speeches, but most of the time was spent discussing resolutions which had been put forth by Amelia Bloomer, Antoinette Brown, and Rhoda DeGarmo. Stanton was elected president of the new organization, while Rhoda DeGarmo was chosen as one of several vice-presidents.

DeGarmo’s belief in the temperance (abstinence from alcoholic liquors) cause led to active participation in that movement in the early 1850s. When Susan B. Anthony was prevented from speaking at a Sons of Temperance meeting in 1852, Anthony began to plan the establishment of a woman’s statewide temperance society. A call was put out and almost five hundred women came to a meeting to form the Woman’s State Temperance Society. At the meeting, held on April 20th and 21st, 1852, Elizabeth Cady Stanton gave several rousing speeches, but most of the time was spent discussing resolutions which had been put forth by Amelia Bloomer, Antoinette Brown, and Rhoda DeGarmo. Stanton was elected president of the new organization, while Rhoda DeGarmo was chosen as one of several vice-presidents.

DeGarmo was also one of America’s earliest women’s rights activists. Her overt work on behalf of women’s suffrage and women’s rights began in 1848, when she was chosen as one of the members of the Arrangements Committee for the Adjourned Convention held in Rochester, New York on August 2, 1848, about two weeks after the Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls. With the rest of the Committee, DeGarmo met in Protection Hall in Rochester on August 1, 1848 to formulate an agenda and select a slate of officers for the Convention. The Committee decided to nominate a woman — Abigail Bush — to preside at the convention, a move opposed by Stanton and Lucretia Mott as “a most hazardous experiment.” In spite of this opposition, the Committee insisted on its choice, and Bush later recounted that:

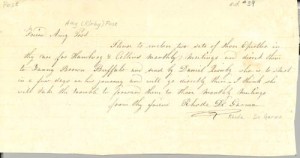

in the vestibule before the meeting my old friends Amy Post, Rhoda DeGarmo and Sarah Fish…at once commenced to laboring with me to prove the hour had come when a woman could preside and led me into the church.

Bush performed her duties with aplomb, putting to rest the uncharacteristic doubts of Mott and Stanton, and proving the wisdom of DeGarmo and the rest of the Arrangements Committee. DeGarmo herself took an active role in the Rochester convention, discussing the proposed resolutions after Stanton had read the Declaration of Sentiments that had been adopted at Seneca Falls.

DeGarmo also had a prominent role in the Monroe County women’s rights convention held in January 1853 and at a statewide convention held in Rochester in November that year. November 1853 also witnessed the marriage of DeGarmo’s daughter, in a ceremony performed by Antoinette Brown. Brown, a women’s rights activist herself, was the newly-ordained minister of the First Congregational Church in Butler and Savannah (Wayne County), New York, one of the first ordained women ministers of a recognized denomination in the United States.

DeGarmo also had a prominent role in the Monroe County women’s rights convention held in January 1853 and at a statewide convention held in Rochester in November that year. November 1853 also witnessed the marriage of DeGarmo’s daughter, in a ceremony performed by Antoinette Brown. Brown, a women’s rights activist herself, was the newly-ordained minister of the First Congregational Church in Butler and Savannah (Wayne County), New York, one of the first ordained women ministers of a recognized denomination in the United States.

DeGarmo’s activity on behalf of women’s rights culminated with her vote in the 1872 presidential election. She was one of the fifteen women, including Susan B. Anthony, who succeeded in both registering and casting their votes. When an official election watcher challenged the votes of the women, DeGarmo, in this instance holding to Quaker beliefs, refused to either swear or affirm an oath, insisting that the fact that she would simply “tell the truth” should be enough.

Rhoda DeGarmo died in 1873, within a year of casting her vote.

Bibliography of Suggested Books & Articles

- Harper, Ida Husted, The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, Indianapolis and Kansas City, The Bowen-Merrill Company, 1898-1908. v. I.

- Hewitt, Nancy, Woman’s Activism and Social Change, Rochester, New York, 1822-1872, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1984.

- History of Woman Suffrage, Rochester, NY.: Susan B. Anthony, 1887., , vols. I, II, IV

- Lutz, Alma, “Susan B. Anthony and John Brown,” Rochester History, v. XV, no. 3 (July 1953).

- McKelvey, Blake, “Susan B. Anthony,” Rochester History, v. VII, no. 2 (April 1945).

- McKelvey, Blake, “Woman’s Rights in Rochester: A Century of Progress,” Rochester History, v. X, nos. 2 & 3 (July 1948).

Bibliography of Suggested Web Sites