Born April 2, 1827

Birthplace Battenville, NY

Died February 5, 1907

Grave Site Mt. Hope Cemetery, Rochester, NY

Contribution Educator and suffragist

Quotation “…taxation without representation is just as great ‘tyranny’ today…as it was in 1776….”

“…until we can establish equality between men and women we shall never realize the full development of which manhood and womanhood are capable.”

Mary Stafford Anthony was born on April 2, 1827, to Daniel and Lucy Read Anthony, in Battenville (Washington County), New York. Her father was a liberal Quaker (Society of Friends) abolitionist, and although her mother had been raised a Baptist, the Anthony family were raised as Quakers. Anthony had three sisters and two brothers. One of her older sisters was Susan B. Anthony.

Anthony’s father was at various times a shopkeeper, the owner and manager of cotton mills, a farmer, and an insurance agent. While the family lived in Battenville, her father, then a thriving mill owner, established a school in his house for his children and many of those in the neighborhood. It was there that Anthony received much of her early education.

During the Panic of 1837, Daniel Anthony lost everything, and he and his family were almost forced to give up all they owned to auction. Their most personal belongings were saved only when Anthony’s uncle, Joshua Read, bid for them and returned them to the family.

In 1839, the Anthonys moved to Hardscrabble (later called Center Falls), New York. When Anthony was seventeen years old she followed the footsteps of her older sister Susan and became a teacher. She taught at a district school in Fort Edward, “boarded ’round” with district families and received $1.50 per week for her labors.

In 1839, the Anthonys moved to Hardscrabble (later called Center Falls), New York. When Anthony was seventeen years old she followed the footsteps of her older sister Susan and became a teacher. She taught at a district school in Fort Edward, “boarded ’round” with district families and received $1.50 per week for her labors.

In late 1845, Anthony moved with her family to a small farm in Gates, west of Rochester (NY). She stayed at home for the next eight years, helping with the farm and the household and studying in her spare time. In 1852, attracted by the preaching of the liberal minister William Henry Channing, Anthony began to attend the Unitarian Church. In later years, she spoke of her reasons for attending the Church’s Unity Club:

Those of you, who when young loved music, can appreciate my pleasure in the change from the long and often silent Quaker meeting, broken at last only by the hand-shaking, to one where instrumental and vocal music was followed by a good sermon, interesting to old and young alike, and then more music. The liberal preaching of William Henry Channing in 1852 proved so satisfactory that it was not long before this was our accepted church home…

In 1854, Anthony decided to return to teaching. She taught one year at a district school and another in a private school at Easton, New York prior to returning to Rochester. She began teaching in Rochester’s public schools in 1856. In 1860, she served a stint as acting principal in one of the City’s public schools. There, she demanded and received pay equal to a man, a highly unusual accomplishment. In 1868, she became principal in her own right of Ward School No. 2 in Rochester. She remained there until she resigned from the profession in 1883.

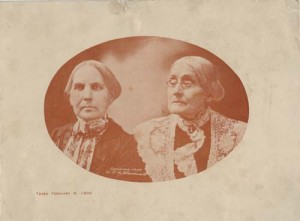

In 1862, Anthony’s father died. The family farm was eventually sold, and Anthony moved with her mother to Rochester, living first on North Street and finally settling at 17 Madison Street. In 1870, Lucy Read Anthony became an invalid, and for the last six years of her life until her death in 1880, she was entirely helpless. Anthony assumed primary responsibility for her care.Photograph of Mary and Susan B. Anthony

In addition to her teaching and caregiving roles, Anthony also proved willing to come to the aid of her older sister Susan. In 1870, when Susan’s journal The Revolution was in financial straits, Anthony not only loaned her sister money to help save the journal; she also spent a sweltering New York City summer working in the journal’s office, while Susan traveled to raise money and attract subscribers.

Susan often expressed appreciation that her younger sister generally assumed the responsibility of caring for ill and dependent family members, thereby allowing Susan to devote her energies to women’s rights activities. The Anthony sisters’ respect and appreciation was mutual, however, and their relationship symbiotic. As a teacher, Anthony applauded her older sister’s work on behalf of women’s rights. In 1870, she sent Susan a gift of $50, saying that the sum was “not a present, merely, but…a debt…for ‘services rendered.’” She noted that “Had there been no agitation for the last twenty years…we teachers might still be working for $1 per week and ‘boarding ‘round’….”

Although Anthony was to remain in the shadow of her famous older sister, she was a suffrage activist in her own right. Her interest in women’s rights, in fact, preceded that of her sister. On August 2, 1848, she attended the Adjourned Convention in Rochester of the First Woman’s Rights Convention and, together with her father and mother, signed the Declaration of Sentiments. In November of 1872, she was one of the women who, along with her sister Susan, voted in the presidential election. Anthony again attempted to register to vote in 1873, this time unsuccessfully. In 1878, she acted as a Monroe County delegate when the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) held its convention in Rochester, New York, to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of the first woman’s rights convention.

Anthony’s mother died on April 3, 1880. Shortly afterwards, Anthony rented out the lower part of the house on Madison Street, living in the rooms upstairs and eating with her tenants. She resigned her position as school principal in 1883.

Anthony stepped up her women’s rights activities in the mid-1880s. She was instrumental in establishing the Women’s Political Club (later renamed the Political Equality Club). It was at her home that a number of interested women gathered in December of 1885; by March of 1886, the organization was fully formed and a president had been elected. Anthony herself was to assume the presidency of the organization in 1892. She served in this capacity for the next eleven years.

Anthony stepped up her women’s rights activities in the mid-1880s. She was instrumental in establishing the Women’s Political Club (later renamed the Political Equality Club). It was at her home that a number of interested women gathered in December of 1885; by March of 1886, the organization was fully formed and a president had been elected. Anthony herself was to assume the presidency of the organization in 1892. She served in this capacity for the next eleven years.

Anthony was to prove an activist president of the Political Equality Club (PEC). During her first year in office, the Club organized a drive to convince the City Council to include a women’s suffrage clause in the City’s new charter. The Club obtained a set of enrollment books and embarked upon a survey of the city in order to provide numbers to influential groups on how many residents favored woman suffrage. Although a partial survey was completed with impressive results, the City declined to seriously consider the suffrage clause.Image of cover: The Poltiical Equality Club

In 1891, Anthony’s sister Susan decided to settle permanently in Rochester, and the Political Equality Club (PEC) helped prepare the Anthony home for the Susan’s return. From then on, Anthony’s housekeeping chores were inextricably interwoven with women’s rights activism, and guests — long term and short term — streamed through constantly. Susan B. Anthony’s biographer wrote,

…friends often urge [the Anthony sisters] to hang out a sign — The Wayside Inn — for it is indeed a hostelry….There is always an extra plate on the table….[I]t is no uncommon thing for three or four guests to arrive a few minutes before supper in response to a pressing invitation from Miss [Susan] Anthony which she forgot to mention…, and the larder always has to be kept in a state of preparation for these ‘surprise parties.’ The three ‘spare beds’ often prove none too many for those who stay from one night to seven or more.

In 1893, Mary Anthony was elected corresponding secretary for the New York State Woman Suffrage Association (NYSWSA). That same year, the state’s suffragists decided to mount an all-out campaign to obtain the vote for New York’s women. The Anthony home became a campaign headquarters. Ida Husted Harper describes Anthony’s domestic situation at the time:

In 1893, Mary Anthony was elected corresponding secretary for the New York State Woman Suffrage Association (NYSWSA). That same year, the state’s suffragists decided to mount an all-out campaign to obtain the vote for New York’s women. The Anthony home became a campaign headquarters. Ida Husted Harper describes Anthony’s domestic situation at the time:

The parlors became public offices; the guest chamber was transformed into a mailing department. Miss [Susan] Anthony’s study was an office by day and a bedroom by night; and even the dining-room and kitchen were invaded.

Anthony herself was in the midst of this activity, working “day and night from December, 1893, to July, 1894, sending out thousands of letters, petition blanks, leaflets, suffrage papers….” In addition to these unpaid duties (she declined a salary), Anthony also took charge of the local canvass of the city in her capacity as President of the PEC. Her results in this effort were lauded as among the best in the State.Image of Mary and Susan Anthony

In 1896, when Susan met Ida Husted Harper, a reporter covering the California campaign, the elder Anthony sister decided to have Harper return to Rochester and write her biography. The house at Madison Street (along with Mary Anthony) was again pressed into service, becoming a workplace for Harper and the stenographers who were hired.

On top of these duties for the sake of the suffrage cause, Anthony became increasingly indispensable to Susan’s daily life. She shopped for her famous sister, kept the house, did her errands, and helped her pack for her innumerable trips.

On top of these duties for the sake of the suffrage cause, Anthony became increasingly indispensable to Susan’s daily life. She shopped for her famous sister, kept the house, did her errands, and helped her pack for her innumerable trips.

Anthony generally preferred to remain in the background, yet her tireless devotion to her sister and to the cause of women’s rights was recognized on the occasion of her seventieth birthday, in 1897. There was a large celebration in her honor, impressive enough to be reported in the Democrat and Chronicle, the local newspaper. Speakers at the occasion included Jean Brooks Greenleaf and Rev. William C. Gannett. Among the gifts received were a purse containing $70 and a diamond pin.

Anthony, a homeowner and taxpayer, believed that women should not have to support a government that did not allow them representation. While she paid her taxes, she wanted it recorded that they were “Paid under protest.” During the year 1897 Anthony began to make written “Protests.” In one of the Protests, dated 1901, Anthony stated that while she was paying her taxes, she believed “…that taxation without representation is just as great ‘tyranny’ today…as it was in 1776….” Her last Protest, written in 1907 (the year of her death) stated in part that she “still” protested “against helping to support a Government manifestly so unjust to one-half of its people.”

In 1900, Anthony again proved herself both a reliable sister and worker for the cause of women’s rights, when she gave $2,000 to the University of Rochester, thereby helping to allow it to open its doors to women. Her sister, desperately seeking funds to meet the University’s deadline, had persuaded Anthony to give what she had intended to bequeath to the university should it become co-educational. Susan B. Anthony had urged her sister, “Give it now….Don’t wait or the girls may never be admitted….”

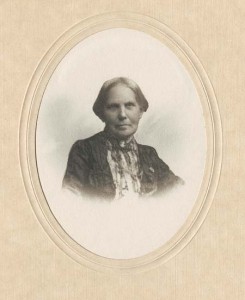

Susan B. Anthony had tried unsuccessfully to convince her younger sister to venture abroad during the former’s trip to Europe in 1883. After much persuasion on the part of her older sister, Anthony did take a European trip in 1899. While there, she visited France, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Ireland, Scotland and England, as well as attending a portion of the International Council of Women’s Photograph of Mary Anthony meeting in London. In 1904, again at the urging of her older sister, Anthony made a second voyage overseas, this time to attend the International Council of Women in Berlin. When the International Woman Suffrage Alliance was formed during their visit to Berlin, Susan B. Anthony was declared its first member, and Miss Mary Anthony was unanimously declared its second.

Susan B. Anthony had tried unsuccessfully to convince her younger sister to venture abroad during the former’s trip to Europe in 1883. After much persuasion on the part of her older sister, Anthony did take a European trip in 1899. While there, she visited France, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Ireland, Scotland and England, as well as attending a portion of the International Council of Women’s Photograph of Mary Anthony meeting in London. In 1904, again at the urging of her older sister, Anthony made a second voyage overseas, this time to attend the International Council of Women in Berlin. When the International Woman Suffrage Alliance was formed during their visit to Berlin, Susan B. Anthony was declared its first member, and Miss Mary Anthony was unanimously declared its second.

Anthony’s suffrage work extended through her seventies and up until her death. In 1905 she traveled to Portland, Oregon with her sister to attend the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) convention. There, at an evening session, she read the Declaration of Sentiments, which she had signed back in 1848. The same year, the sisters held an open house in their home for delegates to the NYSWSA Convention, held in Rochester (NY). In 1906, she accompanied her sister Susan B. Anthony to Baltimore for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) convention, held just over a month before her older sister died. An ailing Anthony traveled to Oregon shortly after Susan’s death — at Susan’s request — to help in that state’s campaign for a women’s suffrage amendment.

In October of 1906, Anthony attended her last suffrage convention, the NYSWSA meeting held in Syracuse, New York. On her deathbed she composed her final message to the NAWSA Convention, which was held in Chicago on February 14, 1907. She died at her home on February 7, 1907. Her funeral service was held at the Unitarian Church. She was buried next to her sister at Mount Hope Cemetery.

Bibliography of Suggested Books & Articles

- Barry, Kathleen, Susan B. Anthony: A Biography of a Singular Feminist, NY: NYU Press, 1988.

- “Death Comes to Mary S. Anthony: Long Life of Activity and Usefulness Ended: Survives Sister Less Than Year,” February 1907.

- Harper, Ida Husted, The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, 3 vols.; v. 1: Indianapolis: Bowen-Merrill, 1899; v. 2: Indianapolis: Bowen-Merrill Co., 1898; v. 3: Indianapolis: The Hollenbeck Press, 1908.

- Harper, Judith E., Susan B. Anthony: A Biographical Companion, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 1998.

- Hewitt, Nancy A., Women’s Activism and Social Change, Rochester, New York, 1822-1872, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984.

- History of Woman Suffrage

- v. 1 – Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds. 2d. ed., Rochester, NY: Charles Mann, 1889 (c1881) (Reprint, Source Book Press, 1970)

- v. 2 -Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds. 2d. ed., Rochester, NY: 1881 (Reprint, Source Book Press, 1970)

- v. 3 -Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds. 2d. ed., Rochester, NY: 1881 (Reprint, Source Book Press, 1970)

- v. 4 -Anthony, Susan B. and Ida Husted Harper, eds., Rochester, NY: 1902 (Reprint Source Book Press, 1970)

- v. 5 – Harper, Ida Husted, ed., NAWSA, 1922 (Reprint Source Book Press, 1970)

- v. 6 – Harper, Ida Husted, ed., NAWSA, 1922 (Reprint Source Book Press, 1970)

- McKelvey, Blake, “Susan B. Anthony,” Rochester History, vol. VII, No. 2, April 1945.

- McKelvey, Blake, “Women’s Rights in Rochester: A Century of Progress,” Rochester History, v. X, Nos. 2 & 3, July 1948.

- Pease, William H., “The Gannetts of Rochester: Highlights in a Liberal Career, 1889-1923,” Rochester History, v. XVII, No. 4, Oct. 1955