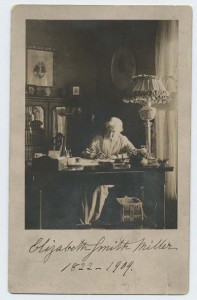

Born September 20, 1822

Born September 20, 1822

Birthplace Geneseo, NY

Died May 22, 1911

Grave Site Peterboro, NY

Contribution Dress reformer and philanthropist

Elizabeth “Lizzie” Smith was born on September 20, 1822 in her maternal grandparents’ home near Geneseo, New York. She was the only daughter to survive infancy. A son, Greene, was born in 1842. Her father was the famous abolitionist landowner and Congressman Gerrit Smith. Her mother was Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, a native of Hagerstown, Maryland, Smith’s second wife.

Smith came from a wealthy family. Gerrit Smith’s father Peter was a partner of John Jacob Astor, a major financier. Ann Carroll Fitzhugh was the daughter of Colonel William Fitzhugh who, with Coloniel Nathaniel Rochester and Charles Carroll, purchased the “100 acre Tract” at the Genesee Falls, later to become Rochester, New York. Smith enjoyed a financially secure life except for a short time during the Panic of 1837, when her family moved from their mansion to a cottage and Smith and her mother worked as clerks in her father’s land office.

Except for that brief period, Smith lived her life in large houses that were known as centers of hospitality and philosophical discussion. Her childhood was spent in Peterboro, New York, where her cousin, Elizabeth Cady [Stanton], later a prominent suffragist, loved to visit. Stanton wrote,

Here one was sure to meet scholars, philosophers, philanthropists, judges, bishops, clergymen and statesmen….There never was such an atmosphere of love and peace, of freedom and good cheer, in any other home I visited.

Stanton remembers that during her girlhood she “spent weeks every year” in Peterboro, engaging in “discussions on every possible phase of political, religious, and social life….” She notes that the “rousing arguments at Peterboro made social life seem tame and profitless elsewhere….” (Stanton, Eighty Years and More, pp. 52-55). What wasn’t widely known at the time was that Smith’s home in Peterboro was also a station on the Underground Railroad.

Smith was educated mainly by her father and governesses, except for a period in 1835-6, when she attended a “manual labor school” in Clinton, New York, and in 1839, when she went to Friends School in Philadelphia. In 1843, at the age of twenty-one, she married Charles Dudley Miller, a lawyer. The Millers had four children born between 1845 and 1856–Gerrit Smith, Charles Dudley, William Fitzhugh, and Ann Fitzhugh (known as “Anne” in later life). After she married, Elizabeth Smith Miller lived for a time in Cazenovia, New York and then in Peterboro, before finally settling in 1869 in Geneva, New York at Lochland, a lakefront estate.

Smith was educated mainly by her father and governesses, except for a period in 1835-6, when she attended a “manual labor school” in Clinton, New York, and in 1839, when she went to Friends School in Philadelphia. In 1843, at the age of twenty-one, she married Charles Dudley Miller, a lawyer. The Millers had four children born between 1845 and 1856–Gerrit Smith, Charles Dudley, William Fitzhugh, and Ann Fitzhugh (known as “Anne” in later life). After she married, Elizabeth Smith Miller lived for a time in Cazenovia, New York and then in Peterboro, before finally settling in 1869 in Geneva, New York at Lochland, a lakefront estate.

Elizabeth Smith Miller is best known for designing what would become known as the Bloomer costume. She describes this as “Turkish trousers to the ankle with a skirt reaching some four inches below the knee.” She began wearing it in 1851, after working in her garden and becoming “thoroughly disgusted with the long skirt…” Shortly after designing the dress, she wore it to her cousin Stanton’s house. Stanton, now a married woman with children in Seneca Falls, admired the costume and herself began wearing it. Amelia Bloomer, a friend of Stanton, also took up the costume and publicized it in the Lily, a temperance journal that she edited.

Many women’s rights advocates took to wearing the Bloomer costume, but they were so ridiculed that after a few years they abandoned it. The tradition was carried on for several years, however, in gymnasiums and sanitariums, including the sanitarium of Dr. James C. Jackson, in Dansville, New York, where it was spread by dress reformer Dr. Harriet N. Austin. Miller herself wore the costume for seven years, even wearing it to receptions and dinners in Washington, D.C. during her father’s term in Congress (1852-1853).

Miller’s reform activities, including her advocacy for women’s rights, lasted throughout her life. As early as 1850, she and her husband signed the Call for the first National Woman’s Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. In 1868, with her cousin, Stanton, she presented a petition to the governor of Pennsylvania on behalf of Hester Vaughn, an English immigrant servant whom she believed had been unfairly accused of infanticide. The same year, she was part of a group of women who sent a letter to the National Republican Convention in Chicago, asking them (fruitlessly) to include woman suffrage in their platform. In 1878, she acted as an Ontario County delegate to Rochester’s thirtieth anniversary celebration of the first woman’s rights convention, sponsored by the National Woman Suffrage Association.

In 1897, a year after her husband’s death, Miller and her daughter were instrumental in arranging for Geneva to be the site of the annual convention of the New York State Woman Suffrage Association (NYSWSA). During this event entertained speakers and many of the delegates in her home. Shortly after this convention, her daughter, Anne, founded the Geneva Political Equality Club, and Miller served as its honorary president for the rest of her life. Because of their many acquaintances, the Millers were able to ensure that the Club had its share of famous speakers, including Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Chapman Catt, Anna Howard Shaw, and of course, Miller’s cousin, Elizabeth Cady Stanton. When the notorious Emmeline Pankhurst — radical suffrage advocate from England — came to speak before the Club in 1909, Miller personally bought tickets to ensure that the women at William Smith College might hear her.

In 1897, a year after her husband’s death, Miller and her daughter were instrumental in arranging for Geneva to be the site of the annual convention of the New York State Woman Suffrage Association (NYSWSA). During this event entertained speakers and many of the delegates in her home. Shortly after this convention, her daughter, Anne, founded the Geneva Political Equality Club, and Miller served as its honorary president for the rest of her life. Because of their many acquaintances, the Millers were able to ensure that the Club had its share of famous speakers, including Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Chapman Catt, Anna Howard Shaw, and of course, Miller’s cousin, Elizabeth Cady Stanton. When the notorious Emmeline Pankhurst — radical suffrage advocate from England — came to speak before the Club in 1909, Miller personally bought tickets to ensure that the women at William Smith College might hear her.

The 1903 National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) convention noted that Miller, along with Susan B. Anthony, had been invited to address the Phyllis Wheatley Club, an African-American women’s club in New Orleans. In 1907, when the NYSWSA again met in Geneva, delegates were once again invited to Lochland, where Miller hosted a memorial service for Mary S. Anthony. Miller also hosted a “Piazza Party” for regional suffragists every year, and she was often gratefully acknowledged for her financial support to the suffrage cause.

Miller’s financial generosity extended to the cause of education. Her money helped to establish schools for African-Americans, and she also gave substantial sums toward the establishment of William Smith College in her hometown of Geneva. There, the Miller House was named in her honor.

Miller was perhaps most fondly remembered by her contemporaries for carrying on the tradition — established by her father and mother in Peterboro — of providing a welcoming environment for reformers and philosophers. Known for her efficient household management, she published a popular book on the subject — In the Kitchen — in 1875. In addition to entertaining suffragists and speakers who came to Geneva for their meetings, Miller’s home was a place of refuge for her cousin Stanton throughout her life. Stanton would often spend weeks on end at Lochland with her family and friends. Towards the end of their lives, Stanton and Susan B. Anthony often spent summers at the estate.

Miller died in Geneva on May 22, 1911, at the age of eighty-eight. Her remains were taken to Buffalo, where they were cremated. View last will and testament.

Bibliography of Suggested Books & Articles

- History of Woman Suffrage

- v. I, (1848-1861) Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds., 2d ed., Rochester NY, Charles Mann, 1889 (c1881) (reprint, Source Book Press, 1970)

- v. II, (1861-1876) Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds., Rochester, NY, Susan B. Anthony, 1881 (reprint, Source Book Press, 1970)

- v. III, (1876-1885) Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds., Rochester, NY, Susan B. Anthony, 1881 (reprint, Source Book Press, 1970)

- v. IV, (1883-1900), Anthony, Susan B. and Ida Husted Harper, eds., Rochester, NY, Susan B. Anthony, 1902 (reprint Source Book Press, 1970).

- v. V, (1900-1920), Harper, Ida Husted, ed., National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1922 (reprint Source Book Press, 1970)

- v. VI, (1900-1920), Harper, Ida Husted, ed., National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1922 (reprint Source Book Press, 1970)

- Barry, Kathleen, Susan B. Anthony: A Biography of a Singular Feminist, NY: New York University Press, 1988. Barry, pp. 328-329

- DuBois, Ellen Carol, Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America, 1848-1869, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1978. Dubois, pp. 144-5

- Garraty, John A. and Mark C. Carnes, eds., American National Biography, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. v. 15, p. 479-480 (biography written by Wendy Gamber)

- James, Edward T., Janet Wilson James and Paul S. Boyer, eds., Notable American Women, 1607-1950, Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press (Harvard University), 1971. vol. 2, pp. 540-541 (bio written by Elizabeth B. Warbasse)

- Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Eighty Years and More: Reminiscences 1815-1897, NY: Schocken Books, 1898, 1971, 1973.

- Turner, Orsamus, History of the Pioneer Settlement of Phelps and Gorham’s Purchase, and Morris’ Reserve…. Rochester, NY: William Alling, 1851 (Reprint 1976 edition).

Bibliography of Suggested Web Sites

- Elizabeth Smith Miller

- Elizabeth Smith Miller (National Park Service)