Born August 17, 1823

Birthplace Farmington, NY

Died Unknown

Grave Site Unknown

Contribution Anti-slavery and women’s rights activist

Catharine A. Fish was born in Farmington (Ontario County), New York on August 17, 1823. Her parents, Benjamin Fish of Rhode Island and Sarah D. (Bills) Fish of New Jersey, were anti-slavery Quakers (Society of Friends) from farming families.

When she was a young girl, her family moved to Rochester, New York. She was educated in Rochester schools and also spent some time in a Society of Friends (Quaker) boarding school. After returning home, she taught her siblings and some neighbors in her own home. She eventually obtained a teaching certificate, and taught in the Rochester public schools.

In Rochester, her parents became active in anti-slavery circles. She joined her family in these activities at a young age. While in her early teens she collected names for anti-slavery petitions and in 1842, she joined the newly-formed Western New York Anti-Slavery Society (WNYASS). In August of 1846 she married Giles Badger Stebbins (1817-1900), an anti-slavery lecturer. The two were wed in the Fourierist Phalanx at Sodus Bay, New York, a utopian community settled by nineteenth century reformers. These communities advocated simplicity, a balance of physical and mental work, and participatory decision-making. They believed that through living this kind of life they would be able to eventually reform all of society, including abolishing the evils of slavery and injustices toward women.

In 1848, Catharine Fish Stebbins attended the first Woman’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York on July 19 and 20, 1848. The Report of that Convention notes that Stebbins was an active participant who discussed the Convention’s Resolutions along with Lucretia Mott, Ansel Bascom, S.E. Woodworth, Thomas and Mary Ann McClintock, Frederick Douglass, Amy Post and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Stebbins also signed the Declaration of Sentiments and contributed a resolution of her own to the Convention. In this resolution, she honored Elizabeth Blackwell, a student at the Geneva Medical College who was soon to become the first woman graduate of a modern medical school.

At the end of this first Woman’s Rights Convention, delegates decided to hold another meeting two weeks later, on August 2, 1848, in Rochester (the Adjourned Convention). In Rochester, Stebbins, Elizabeth McClintock and Sarah Hallowell (Willis) were nominated and elected Secretaries of this Adjourned Convention. Apparently, all three secretaries were unused to speaking at loud gatherings and could not be heard throughout the hall. After a series of cries of “louder” from the audience, another women’s rights advocate, Sarah Anthony Burtis, stepped up and assumed the responsibility of acting secretary for the remainder of the meeting. In spite of her unsuccessful attempts to be heard as Secretary, however it was in this Rochester meeting that Stebbins’ resolution honoring Blackwell was adopted.

During the fall of the same year, Stebbins experienced two profound spiritual changes. In October of 1848, radical Quakers met in Farmington, accepted a document entitled “Basis of Religious Association,” and started a new religious group, the Yearly Meeting of Congregational Friends. Stebbins joined this Meeting, which abandoned the Quaker practice of separate meetings for men and women, in 1848.

The same fall, Stebbins became a follower of the Fox sisters, along with her friends Amy and Isaac Post, Sarah Hallowell (Willis), Rhoda DeGarmo, Sarah Anthony Burtis and her sister, Sarah Fish. The Fox sisters had claimed they heard “rappings” in their home in Hydesville, New York, near Rochester. They said these “rappings” were messages from the dead, and that they, as mediums, could interpret the messages. Eventually the Fox sisters became leaders in the American Spiritualist movement, and Giles Stebbins became a lecturer for the cause.

Stebbins moved to Michigan in the early 1850s. There, she continued in her anti-slavery and women’s rights activities. She was said to have been active in “every plan to forward equality for women” in Michigan.

Stebbins did not abandon the pacifist principles that had been part of her Quaker upbringing. Although she wished to end slavery, she opposed the Civil War, believing that war was not the way to achieve this goal. In this she disagreed with both her husband and her brother, the latter of whom joined the Union army.

Stebbins wrote and spoke about her pacifist abolitionist beliefs on a number of occasions. Yet her opposition to the war did not prevent her from working for its victims. During the Civil War, she was known for participating in attempts to clothe and care for its many refugees.

Stebbins wrote and spoke about her pacifist abolitionist beliefs on a number of occasions. Yet her opposition to the war did not prevent her from working for its victims. During the Civil War, she was known for participating in attempts to clothe and care for its many refugees.

Stebbins remained active in the women’s rights movement after the Civil War and throughout her life. She was an early member of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), formed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony in 1869. She was often on its executive board, and spoke frequently at Congressional hearings.

On March 25, 1871, Stebbins, accompanied by her husband, attempted to register to vote in Michigan and was turned away. She then accompanied Nannette B. Gardner, another Michigan woman who lived in a different ward, in her attempt to register. Gardner, stating that she was a “‘person’ within the meaning of the fourteenth amendment,…a widow, and a tax-payer,” was allowed to register. Stebbins, using Gardner’s success as a precedent, renewed her own registration attempts. She repeatedly tried to register to vote, and was repeatedly rebuffed.

Stebbins staunchly supported Gardner’s right to vote, while simultaneously seeking the same right for herself. On April 3, 1871, she accompanied Gardner to the polls, where Gardner cast her vote. Stebbins again accompanied Gardner to the polls in the fall of 1872, and Gardner again voted. Although Stebbins was not successful in obtaining the right to vote, she did extract the admission from the election Inspectors that “Mrs. Stebbins would have all the required qualifications of an elector, but for the fact of her being a woman….”

Stebbins signed the “Women’s Rights Declaration” read by Susan B. Anthony on July 4, 1876 — the American Revolution Centennial year — in Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. An 1876 Women’s Rights Convention was held the same month in Philadelphia to commemorate the twenty-eighth anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention. While Stebbins was unable to be present at the Convention, she sent a letter dated Detroit, July 17, 1876 to be read to the meeting. There she stated, in part:

Not able to be with you in your celebration of the nineteenth, I will yet give evidence that I prize your remembrance of our first assemblage and of our earliest work….We may well congratulate each other and have satisfaction in knowing that we have changed the public sentiment and the laws of many states….But we are grateful to remember many women who needed no arguments, whose clear insight and reason pronounced in the outset that a woman’s soul was as well worth saving as a man’s; that her independence and free choice are as necessary and as valuable to the public virtue and welfare; who saw and still see in both, equal children of a Father who loves and protects all.

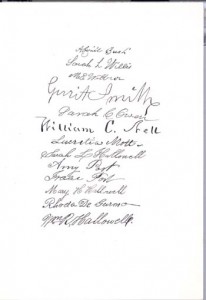

Over twenty years later, Stebbins was to send another letter of description and support to the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) convention of 1898.Image of paper with signatures for Stebbins 50th wedding anniversary

Stebbins was also a personal friend of Susan B. Anthony. In 1889, while traveling back east from a western trip, Anthony stayed with the Stebbins in Detroit. Anthony, in turn, hosted the Stebbins for tea at her own home in Rochester. And the Stebbins invited Anthony to share their golden wedding anniversary in 1896.

Stebbins was also a personal friend of Susan B. Anthony. In 1889, while traveling back east from a western trip, Anthony stayed with the Stebbins in Detroit. Anthony, in turn, hosted the Stebbins for tea at her own home in Rochester. And the Stebbins invited Anthony to share their golden wedding anniversary in 1896.

In 1895 and in 1898, Elizabeth Cady Stanton published one and then another volume of The Woman’s Bible, a highly controversial work which analyzed and criticized those parts of the Bible which demeaned women. Stebbins was on the “Revising Committee” of this work. She remarked in the Appendix that:

The light of a more generous religious thought, a growth out of the old beliefs, impelled the learned ‘Committee on Revision’ to speak the truth in regard to the religious character and work of women, and they have exalted her where before she was ‘degraded.’

It can be said that Catharine A. F. Stebbins spent a great part of her own life speaking “the truth in regard to…women.” In so doing, she helped to assure that women would eventually be “exalted” and recognized as full and equal citizens of the United States.

It can be said that Catharine A. F. Stebbins spent a great part of her own life speaking “the truth in regard to…women.” In so doing, she helped to assure that women would eventually be “exalted” and recognized as full and equal citizens of the United States.

Bibliography of Suggested Books & Articles

- Anthony, Susan B. et al. History of Woman Suffrage, Rochester, NY: Charles Mann & Susan B. Anthony, 1881 & 1902, vols. I, II, III, IV.

- Gordon, Ann D. (editor), The selected papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, c1997-<c2000 >.

- Harper, Ida Husted, The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, (Harper), Indianapolis & Kansas City, The Hollenbeck Press, 1908 , v. II.

- Hewitt, Nancy A., Women’s Activism and Social Change, Rochester, New York, 1822-1872, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984.

- Blake McKelvey,, “Woman’s Rights in Rochester: A Century of Progress,” Rochester History, v. X, nos. 2 & 3 (July 1948).

- Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, The Woman’s Bible, (Great Minds Series, Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1999 (originally published: New York: European Publishing Company, 1898).

- Willard, Frances E. and Mary A. Livermore, eds., A Woman of the Century, Buffalo, NY: Charles Wells Moulton, 1893. Republished by Gale Research Co., Book Tower, Detroit, 1967.

Bibliography of Suggested Web Sites